Interview by Valentina Tanni for Artribune

The following is the English version of the article published in Italian on April 1st, 2021

Hot topic of the moment, NFT and crypto art are the starting point to give the floor to Pau Waelder, critic and researcher engaged in the field of new media art.

Pau Waelder is a Spanish critic, curator and researcher who has been dealing with new media art for many years, with a particular focus on the market. We talked with him about the recent boom in crypto art, NFTs, but also about the relationship between cultural value and market value in contemporary art. Here’s what he told us.

In recent weeks – after the record auction of Beeple with Christie’s and the sale of the Nyan Cat on the Foundation platform – we have read numerous articles announcing the start of a new phase for “the digital art market”. Some have even gone further by even talking about “an era of digital art”. You who have studied the new media art market for many years, what do you think of this sudden boom in NFTs? Are they really the “magic solution” for this type of market, as some claim?

During the last years, auction houses, and particularly Christie’s, have taken the lead in bringing digital art to mainstream attention. In October 2018, Portrait of Edmond de Belamy (2018) by the artist’s collective Obvious sold for over 430,000 USD with the dubious claim of being an artwork entirely created by an artificial intelligence. It made headlines internationally and brought unprecedented attention to AI, with artists scrambling to create GAN-generated artworks. Shortly after, in March 2019, Mario Klingemann’s AI piece Memories of Passersby I (2019) sold for a decent but less spectacular 51,000 USD. The AI craze seemed to cool down quickly, following criticism to Obvious’ work, which was in fact the result of tweaking a GAN programmed by artist Robbie Barat (who was not credited) and putting the print in a gilded frame.

And when did NFTs arrive at auction?

In October 2020, Christie’s sold Robert Alice’s painting Block 21 (2020) for more than 130,000 USD, claiming that it represented a “radical new artistic medium” because, besides being a real, physical painting, it was registered as an NFT. Finally, on March 11, 2021, Christie’s sold Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021) for more than 69 million USD. There was a growing tide of spectacular sales of NFTs, but the Beeple hammer price has sent shockwaves all over the art market. I think this is unfortunate because what everyone is taking about right now is money, not the artworks or what they are about (actually, if you look closely at Beeple’s work, as Ben Davis did for Artnet, it turns out to be quite awful and amateurish). The NFT craze has lead from one unbelievable story to another, from people burning a Bansky print to sell it as an NFT, to the sale of memes, the first tweet, and so forth. I look forward to the Netflix docuseries about the last three months, it will be better than Tiger King! 🙂

Why did Christie’s choose to embark on this venture? Just a marketing operation, as many have claimed?

The purpose of Christie’s and other auction houses is to sell artworks for the highest possible price and widely advertise their sales to attract their customers, both those who want to sell their art and those who want to acquire a unique piece that only a few can own. For this reason, it can be expected that they present the lots as “firsts” and historic opportunities. But when it comes to digital art, this can distort the perception of a wide range of artistic practices and the work of many artists. If a collector buys, say, an artwork that seems to be the first work of art solely created by an artificial intelligence (historic! Groundbreaking!) and then it turns out that it is not, said collector, and potentially others, may blame all of AI art and buy something else. This has not yet happened with NFTs, apparently because there is a strong demand from younger collectors who understand what a digital file is, have fat digital wallets, and are happy paying in cryptocurrency.

But speculation is very high right now, right?

Yes, there is also, in my view, a lot of speculation, given that NFTs are easy to resell (they are sometimes resold within seconds) and the market is hot. This tendency is likely to continue for some time, given that now digital artists with a reputation and a solid body of work are also selling NFTs, which paradoxically can reach higher prices than some of their original, or more elaborated, work. For instance, an NFT by artist Rafael Rozendaal recently sold for 102,000 USD, when one of his famous websites sells for around 10,000 USD. I am glad that the artist makes this kind of money, but from the perspective of an art collector, it doesn’t make sense to pay ten times more for an animated GIF when you could own a website by the same artist, with its own domain and your name inscribed in the html code of the artwork.

What do you see on the horizon for this kind of market? What future can we expect?

NFTs are here to stay and can be a useful way of introducing digital art on the market. By making it easy for any artist to register an artwork as a token on a blockchain, they facilitate selling digital art in limited editions with a guarantee of authenticity and ownership. Non-Fungible Tokens should, in time, be less of a headline and more of a footnote, a technical detail that does not obscure the value of the artwork as a cultural artifact.

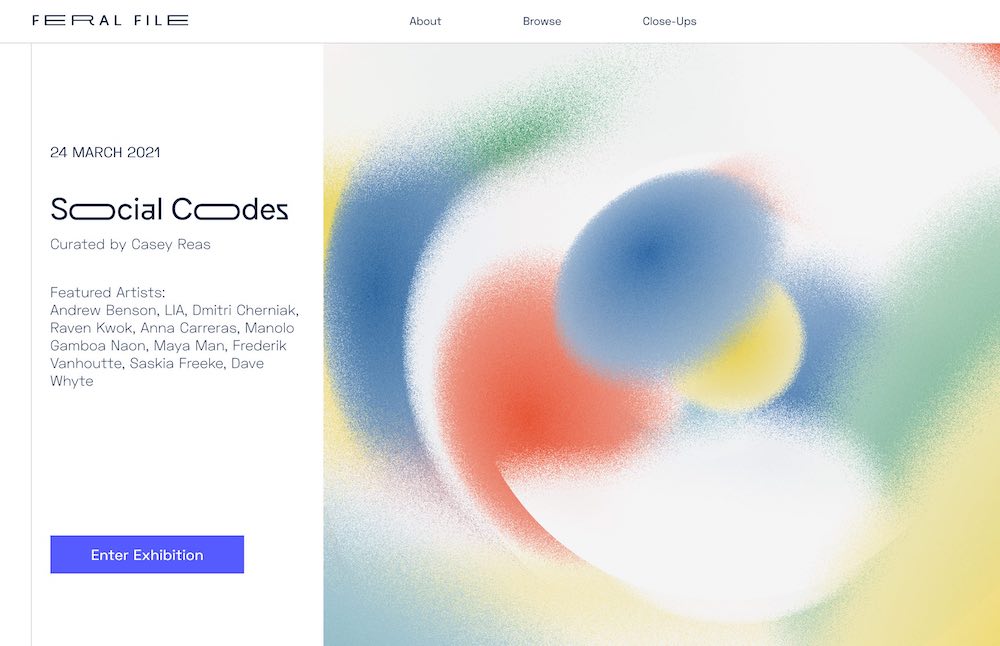

For instance, Feral File, an online exhibition space and publisher of limited edition digital art created by artist Casey Reas, has recently launched its first exhibition presenting and selling artworks by established artists at affordable prices, that are actually minted as NFTs on the Bitmark blockchain. The latter is mentioned in passing in the about section of the website, whereas the artworks are presented as aesthetic experiences freely accessible to anyone, and also available to be collected. Nevertheless, due to the current frenzy over NFTs, only two days after the opening of the exhibition all the artworks are sold out and being resold at exponentially higher prices. While this may sound incredibly lucrative, I fear that it can lead to a dramatic backlash if the market doesn’t settle down a bit. Inflation and speculation are not good bedfellows.

Although digital art has existed now, in different forms, since the 1960s, many people – even professionals in the art world – still seem skeptical about the possibility of acquiring and collecting works of art that consist of digital files (and which are sometimes also accessible online). However, they are not as shocked when it is a performance or a conceptual work that is sold. Why do you think? Is there any form of resistance to the technology itself?

In my opinion, the resistance to accept digital art, and the difficulty in understanding it, do not stem from the technology but from the context in which it is made. Performance art, land art, and conceptual art practices have all emerged within the contemporary art world, by artists who mostly had a background in visual arts and developed their work in art galleries and other venues integrated in the art scenes of influential hubs such as New York, Paris, or London (think, for instance, of Joseph Beuys and the coyote at the René Block gallery in New York). They were supported by collectors, art critics, gallerists, and museum directors. Their work was discussed in art magazines, and even if some of these practices aimed at escaping the white cube of the exhibition space or disrupt the relationship between the artwork and the viewers, their ideas and actions have finally been adapted to the requirements of the art market and the museum.

In contrast, digital art has evolved in the context of art, science, and technology festivals, in science museums and research labs. And while it has also been present in art museums, some commercial galleries, and art fairs, the fact that digital art has been born and nurtured in spaces that are considered “non-artistic,” and linked to narratives that do not align with the predominant discourses in the art world have made it difficult for these artistic practices to be accepted in the mainstream contemporary art scene.

NFT AND ART COLLECTING

So is it a matter of context? Do collectors feel safer about this?

Collectors will preferably acquire artworks that seem reliable in their cultural and economic value, i.e. created by established artists and presented by the most well-known galleries and museums. The nature of the artwork is less important, as long as the collector can feel confident that the artwork is relevant and will increase its value in the future (regardless of whether they intend to sell it or not). A typical example is the performance work of Tino Seghal, which is sold through verbal transmission, without any written document. Therefore, I firmly believe that if Gagosian sold digital art, collectors would buy it without hesitation.

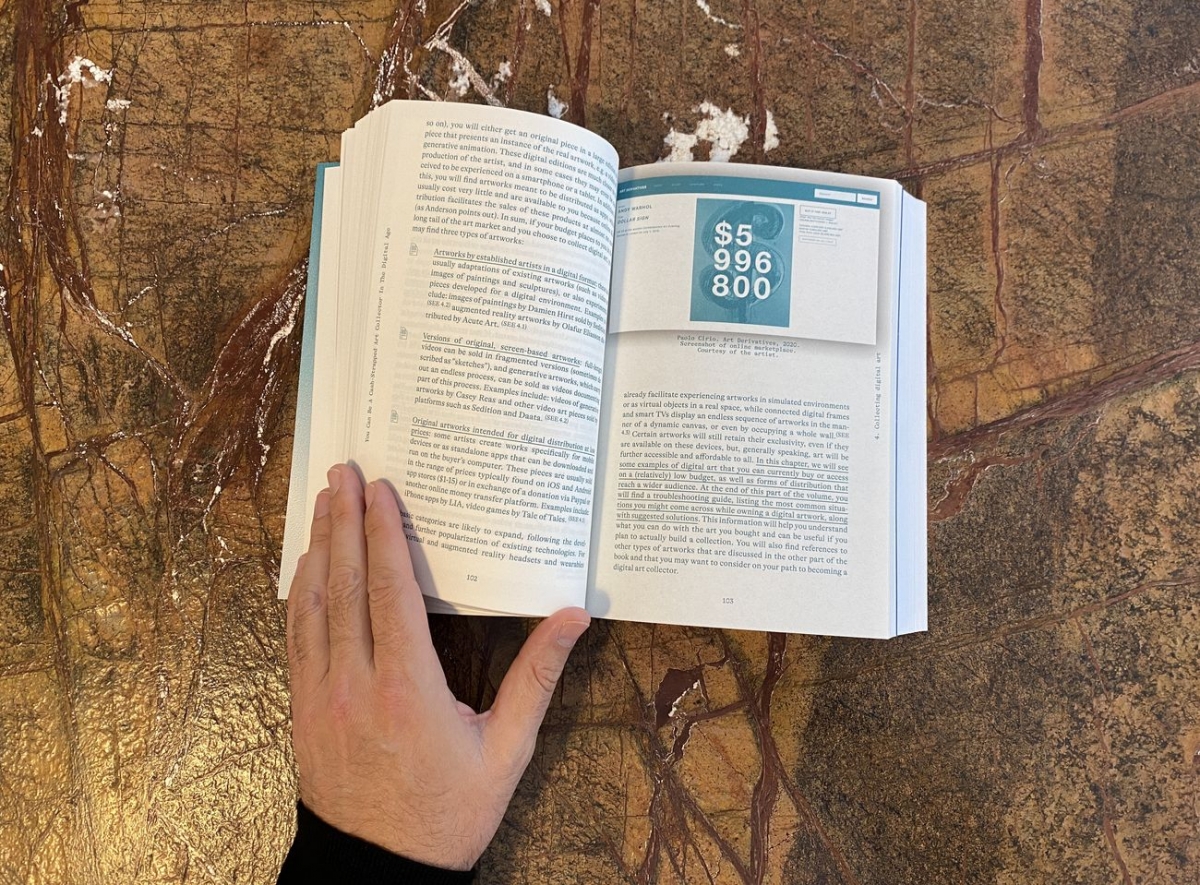

You recently published a very interesting book titled “You Can Be a Wealthy /Cash Strapped Collector in the Digital Age”, which is meant to be a sort of practical guide to collecting contemporary art in digital formats. Can you tell us a little bit more about the contents?

The book is a practical guide to collecting contemporary art using the tools available online and on any smartphone or tablet, with a special focus on digital art and the particular advantages and challenges it presents to collectors. I wrote it last year (partly during lockdown) with the intention of making digital art more understandable, and hopefully attractive to art collectors. The title playfully refers to self-improvement and marketing books, but it is in fact a quite thoroughly documented account of the contemporary art market and the different companies that operate in it, analyzing which services they provide to collectors and what can be expected of them. It is intended to help anyone who would like to collect art, regardless of their knowledge of the art market—or their budget. I thought that a very serious and dry essay would not attract anyone other than a student writing her PhD, so I conceived the book as a guide, which should be easy to read and maybe even fun. I added many diagrams and insets to allow the reader to freely browse the contents.

The book is divided into two parts, right?

Yes, there are two separate (but related) manuals and a troubleshooting guide for collectors of digital art. The first manual, titled ‘You can be a wealthy art collector in the digital age’, addresses all the basic aspects of collecting contemporary art, from finding a motivation to buy art and exploring the art market, to considering quantified analyses of artworks and sharing one’s collection on social media. It also provides insights and advice for collectors of software-based, web-based, and interactive artworks, as well as an analysis of the impact of artificial intelligence and blockchain technologies on art collecting. The second manual, titled ‘You can be a cash-strapped collector in the digital age’, turns to the possible ways of collecting contemporary art on a small budget (from $3 to $300) made available nowadays on online stores, app stores, and digital edition marketplaces. It also discusses the basic aspects of collecting, including motivation, searching for art on a budget, and understanding the type of objects on sale. This manual provides an additional focus on art in digital formats, including art apps, digital editions, and digital art frames. Finally, the troubleshooting guide offers solutions to common questions and problems faced by collectors of digital art, such as digital editions, software art, interactive installations, and web-based, virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) artworks.

Is the goal to increase the population of art collectors?

Yes, I believe that the art world (not just the market) needs more collectors, and particularly collectors who do not buy what everyone else is buying, but who support their local art scene, younger artists, and who are not afraid to buy artworks in unusual formats, be it a software-based piece, a digital file, or a website.

CRYPTOART AND SECURITY

Let’s talk about preservation issues, also. Which are the challenges that a collector of crypto-art for example, could encounter in the future in keeping her/his collection safe and accessible?

There have already been cases of systematic theft of cryptoart, with hackers accessing the digital wallets of collectors and taking tokens worth large sums of money. This, in my opinion, is the consequence of the sudden, massive, and unprecedented attention to a system that wasn’t ready to work at this scale and with such an incentive for criminal activity. Artists have been registering artworks on blockchains for years, also creating artworks as cryptocurrencies (e.g. Carlo Zanni’s ZANNI (Ẓ) cryptocoin from 2018), and selling art in bitcoin or ether. Many sold their artworks for small amounts, so it was quite unlikely that a hacker would steal the artworks. However, if a single token can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, then the whole landscape changes.

So there is a dark side to the NFT world…

There are many things happening right now that show the dark side of NFTs, such as some people minting artworks they found on an artist’s website and selling them as if they were the authors (so called “copyminters”), others artificially inflating the value of a token by selling it to each other, and finally the environmental impact of an activity that produces more than 200kg CO2 for each NFT, equalling the energy consumption of a single person during one month, according to the data collected by artist Memo Akten. When these negative aspects are paired with the promise of making a lot money quick and easy, the result can be catastrophic.

Do you think the situation will change at some point? Is the bubble destined to burst?

I believe that this situation will progressively lead to a more regulated space with a few key players that can offer reliable marketplaces with security protocols to avoid theft and use blockchains based on Proof-of-Stake (PoS) algorithms, which do not require so much computational power and energy consumption. These marketplaces should also be reliable in terms of the authenticity of the artworks they sell, as is the case with art galleries. With these conditions, it should be safe for a collector to buy cryptoart and keep it in her digital wallet, knowing that the artworks are original and authentic.

All in all, it should be noted that even if you lose the token, you still have the artwork: the file with the image, video, or whatever it might be, can be kept in your computer and you can always enjoy it. The token is just a certificate of authenticity that allows you to claim ownership, and therefore resell it. In the actual market, driven by speculation, the token becomes more important than the artwork itself, of course, and no collector would like to be deprived of the ownership and potential profit that could come from selling an artwork she owns (even if she does not intend to sell it). But as much as the cultural and economic value of an artwork can be separated, the proliferation of cryptoart means there is and will be a lot more art to enjoy, even if you can’t own it.